Cells and their lineages are the active agents that translate genetic code into living organisms. They make autonomous decisions, execute complex actions, and collectively achieve architectural goals far beyond the capacity of any individual cell. Our lab seeks to decode these cellular capabilities by "watching" (imaging) cells in both their native environments (in vivo) and controlled, simplified models (in vitro). We focus on three core pillars:

Morphogenesis: How Cells Build Form

Using lung branching as our primary model, we investigate the rules of biological construction. Our approach combines experimental branching organoid systems with computational reinforcement learning to explore the fundamental logic of morphogenesis. By modeling cells as individual agents striving toward specific functional outcomes, we can simulate and identify the minimal rules required to build complex tissues.

Lineage Renewal: The Quest for Cellular Immortality

All good things come to an end – maybe not? Life itself has persisted for 3.8 billion years through unbroken lineages. Embryonic stem cells, for instance, possess an inherent immortality. We study these models to uncover the mechanisms of lineage renewal. Our goal is to apply these principles in two directions: Regenerative medicine to circumvent stem cell exhaustion and prevent age-related decline, and oncology to identify and block the undesired rejuvenation that allows cancer lineages to persist.

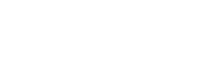

Using live-cell image, we trace lineages of ES cells, and found that, seemingly symmetrically dividing mESCs leverage asymmetric divisions during a sporadic 2C-like state to extend their lineages. By selectively concentrating damage into one daughter cell, the other daughter cell is left in a better state than its mother. See Wang et al., Cell Res, 2026.

Cellular Decision-Making: Navigating Internal and External Chaos

Cells live in ever-changing environments – waves of chemical messengers, fluctuations of temperature, push and pull from neighbours, and up and down of food levels. The inside of cells is even more of a crowded mess – constant fission and fusion of organelles, breakdown and synthesis of large molecules, growing and shrinking of cytoskeleton, and transport of cargos – and all these, happens in a Brownian blizzard. How does a cell process this noise to make precise fate decisions? While genetics has provided the parts list of molecular players, we focus on the spatiotemporal dynamics. We build live-cell imaging tools to quantify these decision-making processes under the microscope, capturing life’s basic unit in action..

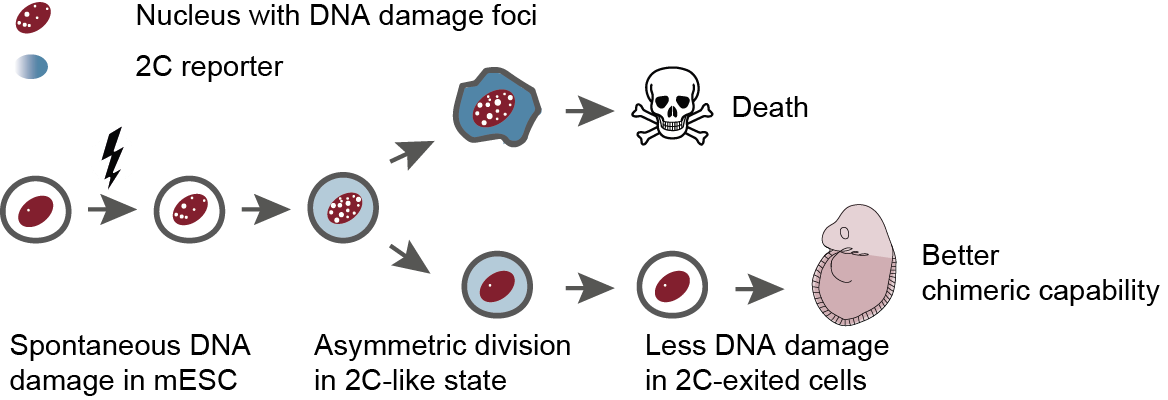

Using live-cell image, we found that, in contrast to textbook models that cells sense growth signal only in G1 phase, cells in fact continuously sense and integrate signals throughout the entire cell cycle. See Min et al., Science, 2020.